From Queenpedia.com

Adapted from article by Andy Davis / John S Stuart

History

Virtually everyone who came into with Freddie Mercury in the late 1960’s tells the same story. Take Chris Smith, a fellow student of Freddie’s at Ealing College, for instance “Right from the start, before he’d even joined a band, Freddie would say, ‘I’m going to be a pop star, you know.’ I remember walking into the West Kensington pub in Elsham Road one day and Freddie was there’ he replied, with his head in his hands. ‘What’s the matter with you? I asked. ‘I’m not going to be a star, I said, ‘You’ve got to be a star, you’ve told everyone. You can’t let them down now. Come on’. And then he stood up, put his arms in the air and said, ‘I’m not going to be a star. I’m going to be a legend!”

Chris smith, who also teamed up for a short while with Brian May and Roger Taylor in Smile, has the distinction of being the first person to collaborate with Freddie Bulsara – as he was then known – on his early attempts at song writing. Another of Freddie’s early musical partners was Mike Bersin, guitarist with Ibex, a progressive blues band from Merseyside, whom Freddie joined in 1969.

“Freddie knew where he wanted to go,” confirms Mike, “That’s why he was an international star. It wasn’t an accident. It happened because that’s what he wanted to be from the moment I first met him. He was a man with a goal and a drive.”

Even with Freddie as their front man, though, Ibex were little more than an amateur outfit, managing to secure just three gigs in the summer of 1969. Freddie then changed their name to Wreckage, and another handful of inauspicious live shows followed. By the end of the year, it was all over; leaving Freddie to team up with another heavy blues band, the Surrey based Sour Milk Sea. He set about moulding them into his ideal, too, but that engagement lasted only a matter of weeks. In April 1970, Freddie achieved the ambition, which had been driving him for more than a year, when he joined Brian May and Roger Taylor in Smile. He changed their name too – to Queen.

In 1974, when Queen had their first hit with ‘Seven Seas of Rhye’, Freddie Mercury was nearly 28. By then he’d been singing on and off, for sixteen years, more than half his life. The story starts a continent away on the East African spice island of Zanzibar, where Freddie was born Farookh Bulsara to Persian parents in September 1946. Zanzibar was then in it’s final throes as a British colony, and Freddie’s father was a High Court cashier for the British government. In 1954, Bomi Bulsara’s job took the family to India, and Farookh was sent to St. Peter’s English boarding school in the hilltop retreat of Panchgani, about fifty miles out of Bombay.

“He talked about his background as if it was repressed and enclosed,” recounted another friend from Ealing College, Gillian Green. “You could tell he didn’t like talking about it. He said he was so glad they had come to England.”

Derrick Branche – who spent five years with him at St Peter’s in India, and went on to star in the 1980’s ITV Sitcom “Only When I Laugh” – recalled that that “It was the best place I can think of for a kid to go to school. I can think of nothing ugly about the place or time we had there.”

In 1958, five friends at St Peter’s – a 12-year old Farookh, who’d by now acquired the nickname ‘Freddie’, Branche, Bruce Murray, Farang Irani and Victory Rana – formed the school’s rock ‘n’ roll band, the Hectics.

“It was as the piano player in the Hectics,” says Branch, “that Freddie first performed as a musician, cranking out a mean boogie woogie even at that tender age. We would play at school concerts, at the annual fete, and at other such times when the girls from the neighbouring schools would come along and scream, just like they’d obviously heard that girls the world over were beginning to do when faced with current idols such as Cliff Richard or Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Fats Domino, these last two being Freddie’s and my particular favourites.”

Freddie was shy in the Hectics, and was content to let Bruce Murray bask in the ‘limelight’ as front man. The band wasn’t allowed to perform outside the school grounds, but little else is known about them.

“He never really talked about his life other than being in England, ever.” Says David Evans. “ To anyone. I always found it much more romantic than he did, but he’d say ‘Don’t be silly, dear!’ I’d ask him, ‘what was it like in Zanzibar? It must have been so exciting,’ and he’d say ‘Dirty place! Filthy place, dear.’ There’s not much you can say after that, is there?”

“He really wasn’t into acknowledging that part of his life at all”. Strangely, even when he bumped into Derrick Branche again in London, he wasn’t particularly overjoyed. “He wasn’t averse to it, but he didn’t suddenly embrace Derrick as a long-lost friend. They didn’t take up their friendship at all.”

Freddie left St. Peter’s in 1962, and in 1964, when Zanzibar won independence from Britain and civil unrest threatened, the Bulsara family moved to England, arriving in Feltham, Middlesex. Freddie, the seventeen, studied art and fashion ‘A’ level at Isleworth Polytechnic before moving to Ealing College of Art in the spring of 1966.

He commuted from his home in Feltham most days, or crashed on the floor at a flat in Kensington rented by Chris Smith. “Freddie was always interested in music,” remembers Paul Humberstone, a flatmate of Smith’s and another student at Ealing. “The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix were his favourites, he was always playing air guitar and doing his Hendrix impersonations. He used to do a sort of showbiz stance. We thought he was joking around to amuse us. We used to call him Freddie Baby, and he’d say, ‘Don’t worry; I’ll be big one of these days. I’ll be a real star’. No-one believed, because no one had heard him sing at that point.”

Freddie’s scene soon revolved around Paul and Chris’ flat in Addison Gardens, London W14, and by the beginning of 1969, around another flat in nearby Sinclair Road, which was occupied by, among others, Smile’s Roger Taylor. Freddie was introduced to Smile by the group’s singer Tim Staffell, who also studied at Ealing. “ It wasn’t that I actively brought Freddie in,” claims Tim, “it was just that you naturally fall in with people of a similar cultural leaning.”

“Everyone around Smile used to gravitate towards Freddie, even though he wasn’t in the band.” Adds Chris Smith – who had actually been a founder member of Smile. “He’d say to me ‘I wish I was in your group’, and ‘If I was in this band, I wouldn’t do it that way.’” Inspired by Smile, Freddie began to experiment with music for the first time since leaving India. He initially began to practise with Tim, a friend called Nigel Foster, who was a straight-laced advertising student, and with Chris Smith.

“We used to have jam sessions in the college,” recounts Chris. “The first time I heard Freddie sing I was amazed. He had a huge voice. Although his piano style was very affected, very Mozart, he had a great touch. From a piano player’s point of view, his approach was unique.”

Chris and Freddie also attempted to write songs together. “I was doing a music degree at the same time,” reveals Chris, “and I had the keys to the music department. Freddie used to get me to open it up, where we’d hammer away at the piano, trying to write. We were hopeless. He’d say, ‘How come Brian and Tim can write songs like ‘Step On Me’ and ‘Earth’?’. We were in awe of the fact they could do this it was quite magical. Only the Beatles could really write proper tunes. Freddie and I eventually got to write little bits of songs, which we linked together like ‘A Day In The Life’. This makes sense when you consider ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. You know: ‘woke up, fell out of bed’, and ‘I see a little silhouette of a man.’ It was an interesting way of getting from one piece in a different key signature to another. But I don’t think we actually finished anything. There was a cowboy-type song called ‘The Real Life’, which was actually reminiscent of the first part of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. That was the chorus at that time, although it could have been one of Brian’s songs. I remember that distinctly. Freddie certainly taught me a lot at those sessions. He had a great, natural sense of melody. I picked that up straight away. For me that was the most interesting aspect of what he was doing.”

Freddie left Ealing College in June 1969, with a diploma in graphic art and design, and a few commissions to draw ladies’ corsets for adverts in local newspapers. He moved into Roger Taylor’s flat in Sinclair Road, and that summer opened a stall with Roger at Kensington Market, initially selling artwork by himself, and later Victoriana or whatever clothes, new and second-hand, he could lay his hands on.

“He was quite flamboyant then,” says Chris Smith, who recalls Freddie’s taste beginning to embrace the pop chic of satin, velvet and fur. “I remember buying a pair of red trousers in Carnaby Street and turning up at college thinking they were really sharp, but Freddie was there in a pair of crimson, crushed velvet ones like Jimi Hendrix wore – a bit of a dude. He was sitting there reading the ‘Melody Maker’ and he saw me, glanced down, and didn’t say a word.”

Freddie lived for music, and in August that year he seized upon the opportunity he’d been waiting for – to sing in a band. Too impatient to form one of his own, he did the next best thing and found himself a ready-made outfit. His quarry was Ibex, a Merseyside-base trio comprising Mike Bersin (guitar and vocals.) and John ‘Tupp’ Taylor (bass and vocals) and a drummer by the name of Mike ‘Miffer’ Smith. Bersin and Taylor had played together since 1966 in a band called Colour, earning a local reputation with a series of gigs at such noted venues as Manchester’s ‘Twisted Wheel Club’ and the Cavern Club in Liverpool. They’d even acted as pick-up band for British blues singer Jo-Ann Kelly.

“Under the influence of Cream,” reveals Mike Bersin, “we realised that you only needed three musicians: one at the low end, one for the middle and one for the high, and one for the rhythm. You’d then solo endlessly until everybody fucked off to the bar.” “We were progressive,” adds John ‘Tupp’ Taylor. “We wore hairy fur coats and grew our hair. We played a few improvised instrumentals which gathered form and almost became songs, but we never got around to completing any lyrics or melodies.”

In may 1969, Ibex played their debut in the small Merseyside town of Penketh, and prior to meeting Freddie, had packed off a demo tape to the Beatles’ Apple label, which resulted in little more than ‘Miffer’ Smith becoming enough of a celebrity to warrant a write-up in the local ‘Widnes Evening News’

Mike Bersin: “We persuaded Mick to pack up his job as a milkman and go down to London to make it in the music business. We had a Comma van and a load of phone numbers. The morning after we arrived we all piled into a phone box. Our roadie, Ken Testi, dialled this number. We were all crowded around the mouthpiece and we heard him say, ‘ Hello, is Chris Ellis there, please?’ and this very frosty-voiced woman on the other end said ‘Yes, this is Chrysalis’. That was the level of our sophistication.”

“We met the members of Smile at a pub called the Kensington,” recalls ‘Tupp’ Taylor. “We saw them play a couple of times and they were really good. They had a great vocal-harmony thing going. Tim Staffell, their bass player, was a really good singer, and Freddie was a mate of theirs. We’d all sit around and have amazing vocal sessions singing Bee Gees, Beach Boys and Beatles songs. We could do great harmonies because there was three of them in Smile, myself, Mike Bersin, who’d chip in, and Freddie, of course.”

At this point, it was common knowledge among the Smile crowd that Freddie was desperate to get into Brian and Roger’s band. Perhaps joining Ibex might be a way in.

“Freddie hadn’t quite persuaded Smile to take him on as a vocalist,” confirms Mike Bersin. “They thought they were doing OK as they were. So he said, “You know what you guys need, and that’s a vocalist.’ He was right, too, as John Taylor recalls: “I wasn’t the world’s greatest singer by any stretch of the imagination.” And as Ken Testi reveals “Mike had never been confident about his singing, but had been pushed into it.”

Freddie first met Ibex on 13th August 1969. Such was his enthusiasm, that just ten days later, he’d learned the bands’ set, brought in a few new songs, and had travelled up to Bolton, Lancashire, for a gig with them – his debut public performance. The date was 23rd of August, and the occasion was one Bolton’s regular afternoon ‘Bluesology’ session, held at the town’s Octagon theatre. For Ibex and friends it was the event of the summer. No fewer than 15 bodies, including Freddie, Ken Testi, and the band’s other roadie Geoff Higgins, Paul Humberstone, assorted friends and girlfriends, plus Ibex’s instruments were squeezed into a transit van borrowed from Richard Thompson, a mate of Freddie’s who’d previously drummed in 1984 with Brian May and Tim Staffell.

The gig, booked by Ken Testi before Ibex had left for London, provided a forum for amateur and semi-professional outfits to play, ‘on the understanding that no fees are available though nominal expenses can be claimed from the door takings”. Peter Bardemns band, Village, preceded Ibex on stage and the gig took place ‘in the round’, with the seating placed around the circular stage.

The following day, Ibex appeared in the first ‘Bluesology pop-in’, an open-air event on the bandstand in Bolton’s Queen’s Park. On the bill were local band Back, another called Birth, Spyrogyra, Gum Boot Smith, The White Myth, Stuart Butterworth, Phil Renwick and, of course, Ibex. In a report published the day before the Bolton Evening News wrote ‘The last named act make a journey from London especially for the concert. The climax of the whole affair will be a supergroup, in which all the performers will play together. If the weather is fine the noise should be terrific”.

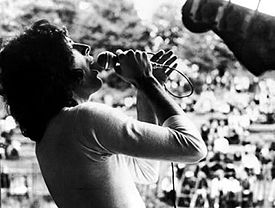

Remarkably, for such a relatively inauspicious event, Freddie’s first-ever public performance was extremely well documented. There were at least three photographers present, and the proceedings were covered in Bolton’s Evening News for the second time on 25th August. This even featured an uncredited photograph of Freddie, with the caption: ‘One of the performers gets into his stride’ If Freddie wanted to be a star he was going about it the right way.

“Freddie really loved going up to Bolton to play with Ibex,” remembers Paul Humberstone. “He was really on form. The band was very basic, but good. They did very reasonable cover versions, and were very loud. That was his very first outing with the band, but Fred struck his pose. Remember him doing ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’? He was like that only without the eye makeup.”

“Freddie was shy offstage,” recalls Ken Testi, “but he knew how to front a show. It was his way of expressing that side of his personality. Everything on stage later in Queen, he was doing with Ibex at his first gig: marching from one end of the stage to another, from left to right and back again. Stomping about. He brought dynamics, freshness and presentation to the band that had been completely lacking previously.”

Mike Bersin agrees: “As a three piece, we’d thought it was sufficient to play fairly basic music and not worry too much about stage craft. Freddie was much better at putting on a show and entertaining people. That was pretty radical for us. I thought that’s what the light show was for, you know, we make the music and the audience can watch the pretty coloured bubbles behind us, but Freddie was different. He was always a star. People used to pull his leg about it when he had no money, one pair of trousers, one T-shirt and one pair of boots. He’d look after them all really well and people would say, ‘Here comes Freddie, the star’.”

“I don’t think Freddie developed,” reckons John ‘Tupp’ Taylor. “The first day he stood in front of that crowd, he had it all going. It seemed as if he’d been practicing for years to be ready. We’d only ever sang together as mates before that. We’d never done anything by way of trying it out. He was going to be in the band and everyone was happy with that. Once Freddie was in, we changed in loads of different directions. We began to play ‘Jailhouse Rock’, for a start! I think that was the first thing we did with him on stage.”

Back in London, a revitalised Ibex began to make plans. “Freddie and the band very quickly became inseparable,” remembers Ken Testi. “They were spending large parts of their time together, working out a new set which included different covers and some original stuff.”

Mike Bersin: “Freddie was the most musical of all of us. He was trained on the piano, and he could write on the black notes. He said ‘We’re never going to get anywhere playing all this three-chord blues crap, we’ll have to write some songs’. A couple of things came out of it, but they’ve all vanished now. I can’t imagine they would be very satisfactory anyway – largely because he was working with me, and my understanding of music was incredibly rudimentary. We used to argue about whether we should put in key changes.. I’d say ‘What do you want a key change for?’ And he’d say that it made a song more interesting, it gave it a lift. I’d think ‘Why has he got this thing about gratuitous key changes?’ The idea of changing the key of a song just because it made it more interesting to listen to was really alien to me.”

That said, Geoff Higgins remembers at least one decent Bulsara-Bersin tune: “ They did a great song called ‘Lover; the lyrics used to go, ‘Lover, you never believe me’ and Fred later turned it into ‘Liar, you never believe me’ It was almost the same tune, but not quite. In fact it was similar to ‘Communication Breakdown’, they used to rip off Led Zeppelin a lot.”

Before they knew it, however, the summer was over and it was September. Mike Bersin returned to Liverpool to begin his pre-diploma years at the local art college, at what is now John Moores University. With nothing better to celebrate than the new term, the pre-dip freshers threw a party, and who better to provide the entertainment than Mike’s band, Ibex? Subsequently Ibex’s third and final gig took place on 9th September 1969 at the Sink Club in Liverpool, a former soul-blue hang out in the basement of the Rumbling Tum – a place Ken Testi remembers as a “pretty dodgy, post beatnik café”. The club was situated on Hardman Street, which runs parallel to Mount street, the site of Paul McCartney’s new LIPA building, and was a small venue. “If you got thirty people in there would have been a squash,” recalls Ken.

While Freddie’s trip to Bolton with Ibex was photographed, unbeknown to Queen historians these past 27 years – and indeed to friends and members of the band – Ibex’s appearance at the Sink was recorded. Hazy memories and a cluttered attic have obscured this amateur quality time capsule of Freddie for nearly three decades. What’s more the recording pre-dates the earliest known live tape recording of Queen (the Marquee, 20th December 1972) by more than three years.

Ibex’s roadie, Geoff Higgins, is the man behind the mono tape recorder and the rediscovery of a lifetime. He picks up the story: “I had a Grundig TK14 reel-to-reel machine. We used to record almost everything, and practically all of it is now gone. That night I just thought I’d take it along and tape the band. There was no other reason for it. You don’t expect to end up in the history of one of the biggest acts in the world. We didn’t hold those tapes as being precious. Although I’ve kept everything of Mike’s since!”

He continues: “I had two beer crates as a table, with my tape on top of them and a little old fashioned mono, crystal microphone hanging down by it’s own wire. That’s why the tape is such chronic quality. Imagine being in the audience and looking at the stage, I would have been by a pillar on the right of, and slightly on front of, the stage. That’s why the bass is so loud, because Tupp was on the right hand side. Mike was on the left. Miffer in the middle, and Fred out on the Floor in front of the stage, because there simply wasn’t enough room for a singer as well.”

The tape runs for thirty-five minutes and demonstrates Ibex’s love of Cream and Jimi Hendrix, as well as Freddie’s favourite of the day, Led Zeppelin. It opens half way through the band’s reading of Cream’s ‘I’m So Glad’ complete with Tupp Taylor’s dextrous bass solo before diving into a full throttle reading of Zeppelin’s ‘Communication Breakdown’, with Freddie’s towering falsetto homage to Robert Plant earning the band a smattering of applause. Freddie’s vocal extemporising on the next track, the Beatles ‘Rain’, vindicates stories of an untried singer with the confidence to launch himself with his own style. Cream’s apocalyptic ‘We’re Going Wrong’ follows with ‘Miffer’ Smith’s Ginger Baker-like drumming rising and falling beneath Freddie’s undulating vocals. Guitarist Mike Bersin shines on ‘Rock Me Baby’, the blues standard popularised by Jimi Hendrix, although the version owes more to the one found on Jeff Beck Group’s ‘Truth’; at one point. Freddie echoes Bersin’s wah-wah with his own ‘wow-wow’ adlibs.

The tape pause here and restarts towards the end of a strut through Hendrix’s ‘Stone Free’ an extended stab at Freddie’s perennial favourite, ‘Jailhouse Rock’, leads into an accomplished power blues blast through Creams ‘Crossroads’. Freddie introduces the next number, one of his compositions, called ‘Vagabond Outcast’. It’s reminiscent of the Queen rarity, ‘Hangman’, and although it’s under rehearsed, it’s similar in style to Ibex’s better-known covers, and earns the band another ripple of applause. Mike and John re-tune their guitars before ‘We’re Going Home’, during which Freddie’s voice can be heard half-taking, half ad-libbing, beneath the low murmuring of ‘Tupp’ Taylor’s bass solo. Freddie than re-emerges, exploding with an alarming rock shriek as the song draws to a close.

It’s a fascinating, if slightly ragged performance, but a crucial early document of one of rock’s greatest stars. “Everyone was incredibly competent in the band,” agrees Geoff Higgins. “There were no slackers. They weren’t rubbish by any means. I know this is a poor recording, but these guys were good.”

Geoff has a further revelation, which called to mind Paul McCartney’s presence in the audience at the first-ever recording of John Lennon with the Quarry Men back in 1957. “Smile were in Liverpool that night… playing another club, possibly the Green Door. And because we were at the Sink, they came down to see us.” The rest of the story is almost too good to be true. Brimming with encouragement for their flamboyant friend Brian May and Roger Taylor wasted no time in joining Freddie on stage (or as near as they could get.) They probably bashed out a few Smile numbers and this occasion marked the first time the three of them played together in front of an audience. “We virtually had Queen in there,” remarks Ken Testi, “although of course we didn’t know it then.” However, here’s the sting: although Geoff Higgins’ tape recorder was still only yards away at the time, the tape ran out before the three musicians had the chance to play a note together.